[MedArtSal] Conti Vecchi saltworks in Sardinia, a model of nature and production combined in perfect harmony

It is said that the engineer Luigi Conti Vecchi asked if Sardinia was touched by the mistral. A curious doubt to be thought in front of the large square that leads to his salt pans, where the north-west wind upsets the tufts of palm trees, sending a rustling sound through the air, and from the bottom it smoothly snatch away scent of rosemary. Clouds broken into flocks run through the blue.

Of Sardinia the engineer had known only the men, the small emaciated “devils” who, dashing in assaults from the First World War trenches, showed the pride of the ancient agricultural and pastoral world. "Too big to be conquered, too small to be independent" commented many years later the Tuscan general who before the war had built bridges and aqueducts around Italy, and who, after the war’s massacre, wanted Sardinia as the theater of his demiurgic work made of sea, earth, men and salt.

In 1919 his project responded to the state ban, and won it. Thus began the huge transformation which would have thrusted the sea where the fresh water infested with malaria was. On the banks of the Santa Gilla pond, evaporating basins and salt boxes, offices, workshop, chemical laboratory, workers and managers houses, school and church appeared in a few years. An English garden city, an Olivetti factory ante litteram, a colonial microcosm of organization, an intertwining of work and nature.

Conti Vecchi died in 1927, year of the first harvest. His mission passed to his son Guido, and so the profits of what would quickly become the third salt pan in Europe, the second in Italy after that of Margherita di Savoia in Puglia. 2700 hectares capable of delivering up to 300,000 tons of white gold and magnesium, plaster, potassium and the gillite, an insulation material kneaded here for the first time that ended up in the theaters and cinemas of Cagliari, which in those year was opening itself up to modernity.

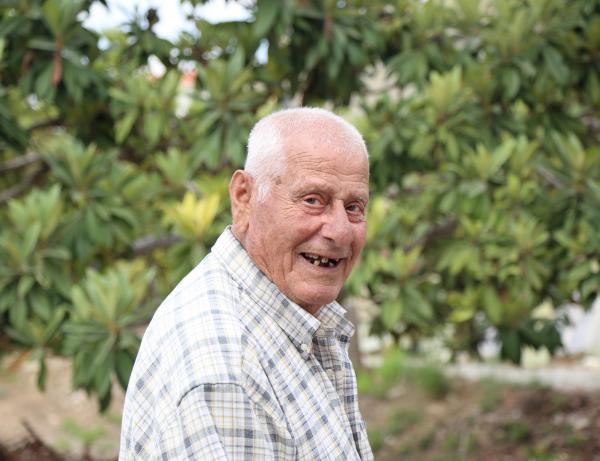

The families of five hundred workers lived in the village, whose fragile construction material did not resist to the passing of time. For each house a kitchen with fireplace, a room, a bathroom and courtyard. A humble luxury for those times. But from September to November, and sometimes until Christmas, for the harvest, the salt pan was filled with seasonal workers, up to 1500 men burned and blinded by the sun, armed with a pickaxe to detach the precipitated salt from the bottom of the vast salt boxes. “In Assemini, those who are eighty at least once in their life have been seasonal salineers. Over the decades the town has established a visceral relationship with the saltworks", explain Giulia Deangelis and Emanuele Masillo, the FAI (Italian Environment Fund) who manage the reception, guide visitors, keep the administration in order, protect nature and memory of this vast, open-air monument.

FAI-Saline Conti Vecchi

Over the decades, the salt pan passed from Conti Vecchi's grandchildren to Rovelli’s IMI, and in 1984 to the Italian state, which later entrusted it to ENI. It is the first time that FAI manages an asset in collaboration with a production business. Offices and work environments, arranged around the internal square, have been restored to their authentic condition. In the director’s office a display case preserves a large crystal of salt from the first harvest, the catafalques of typewriters and tape recorders, the register of operations written in sinuous ink: "50 kg of magnesium sulphate, paid". Outside the window an offcut of the lagoon, and in the distance Cagliari, its row of pastels descending to the sea. In the adjacent room there is the large historical archive (object of a reorganization plan by the FAI) and an ancient drafting machine, the wooden matrices of the fundamental mechanical elements, which reproduced here guaranteed autonomy and efficiency to the salt works. And also the "costs and accounting" office, the chemical laboratory full of stills and the old carpentry where a video projected on the walls describes the entire production process, the large mechanical workshop and the splendid documentary on the history of the salt pan, a vision of the engineer Conti Vecchi embedded in the history of Cagliari and Sardinia.

An industrial and agricultural archeology complex if, as Carlo explains while driving the rubberized train that leads visitors to the natural heart of the salt pan, "the sun and wind affect the harvest, the mountain of salt is a barnyard, the salt worker is a farmer of the sea". The mighty lump of collected salt imposes itself on the eyes, immaculate against the sky like a heavy cloud. A path dug on the side of the strip up to the top, for over time the ridge becomes so hard that it must be shaken with picks. Then the salt boxes parade, the magnesium foam gathered on the banks by the mistral, the pink color of the salinity that will become red like blood when the harvest comes, in November.

Beyond the evaporating basins nature begins to live again. The pond framed by low earthen ballasts, rushes and willows, the reeds that breathe in the low salinity water, the colonies of the flamingos, motionless or oriented towards the southeast, in favor of the wind. The gulls, the shelducks, the marsh harrier, the mallard and even a pelican met a few days ago, during one of the excursions. Santa Gilla is one of the most important wetlands in the Mediterranean basin, a Special Protection Area (SPA) and a site protected by the Ramsar convention since 1977. There are about 50 bird species that inhabit this corner of the pond. They rise in flight, pronounce themselves in a verse, settle down again. Everything else suddenly becomes remote.

Those of Conti Vecchi belong to the group of Mediterranean salt pans that are under analysis by the international project "MedArtSal".

This article originally appeared on MedSea Foundation website, partner of the project MedArtSal.