LIVINGAGRO for Mediterranean agroforestry, new Episode of the series for discovering Greek innovations included in the dedicated Catalogue

THE LIVINGAGRO INNOVATIONS CATALOGUE FOR GREEK AGROFORESTRY

Having identified potentially useful innovations, the partners of LIVINGAGRO project developed a dedicated Catalogue intended to provide an overview of some of the innovations that may be useful to stakeholders involved with multifunctional olive systems and grazed woodlands, in order to help bring together economic stakeholders and innovators who may be able to collaborate to solve common problems. This activity included assessing the stage of readiness of a potential innovation, as well as which type of challenges it addresses. Taking into consideration the needs expressed by stakeholders, the research team of the Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Chania (MAICh) and the technical team reviewed the information provided. Following this review, the working group went back to the innovators to address questions and fill in gaps, then incorporated the responses into the innovation descriptions.

Introduction to Section 2 of the Catalogue concerning intercropping and preparation for climate change in olive groves

Traditionally, olive groves in Greece have included plants such as legumes, cereals, herbs, vegetables, walnuts, grapevines, and truffles. Such a combination of two crops grown at once on a plot of land is known as intercropping. When it includes trees and an annual crop, it is also a type of agroforestry. The traditional agroforestry practice of intercropping offers many benefits over a monoculture--benefits for the soil, the farm, the broader environment, and (as a result) the farmer. Recommending that olive farmers consider innovating by adapting new, improved versions of traditional agroforestry practices, numerous scientists now provide specific advice to help farmers achieve the greatest possible benefits.

Intercropping increases olive groves’ sustainability by adding to their biodiversity and stabilizing the soil, thus reducing trees’ vulnerability to pests, diseases, and climatic stresses. The greater diversity in plant life enables a larger variety of organisms in the soil, as well as more beneficial insects, pollinators, and birds. With intercropping, the soil benefits from increased porosity, improved drainage, less erosion, and decreased nitrogen and phosphorus leaching, which means fewer valuable minerals lost and less pollution of groundwater and surface water. Fewer pesticides and nitrogen fertilizers are required, and olive trees tend to be healthier, which benefits the planet and the farmer. In addition to saving money on pesticides and fertilizer, farmers may also benefit financially both by producing higher quality olives and by harvesting a second crop. They can either sell this product (as in the case of the recently popular avocados) or use it as a natural soil enricher or an animal feed (as with legumes).

One of the most important crops for the Mediterranean region, the olive tree will be subject to increasingly harsh abiotic stresses due to climate change in the coming years. Abiotic stress comes from environmental conditions that can harm plants and reduce their growth and yield, such as extreme temperatures, soil salinity, and drought. (Biotic stress, on the other hand, is caused by living things such as insects, weeds, bacteria, viruses, or fungi.) Shifting cultivation zones, depletion of organic matter, desertification, degradation of water resources, and other challenges make it imperative to prepare for the future, for example by intercropping and by using trees that can resist the effects of climate change.

Presentation of Innovation 7: Intercropping of olive trees and vetch

Background

Traditionally, olive groves were co-cultivated with cereals and legumes in Greece. This type of land use lost favor for a time, but today the co-cultivation of olives with other useful plants has regained the old interest, since it offers many advantages to farmers and the environment with minimal cost and effort.

Keywords

Olive growing, olive cultivation, olive trees, nitrogen-fixing plants, natural fertilization, Koroneiki, legumes, vetch, intercropping, agroforestry, co-cultivation, allelopathy, erosion, biodiversity

Methodology

After the olive harvest, from late December to mid-January, a legume is sown, preferably vetch, in the area under the crown of the tree, leaving only the base of the trunk clean. For this, approximately 300 grams of seeds are required for each tree. If there are weeds, they should be removed before sowing using a brush cutter, unless the weeds are Oxalis pes-caprae (African wood-sorrel, Bermuda buttercup), a common beneficial weed which may be left in the grove when vetch is planted. The vetch grows during the rainy season. At the end of March, when it blooms, the vetch should be cut near the soil level with a brush cutter. The cuttings can be left to decompose where they fall, or they can be incorporated into the soil. If there are branches left over after tree pruning, the branches and cuttings can be shredded together before incorporation into the soil (or shredded and left on the soil surface as mulch). In each case, the cuttings will help enrich the soil.

Specifications

The whole process is simple, quick, and inexpensive. Irrigation is not necessary after sowing, because the rainfall at that time of year is generally sufficient for vetch to thrive.

Impact

1. Increases the quality of the olives

2. Saves money by reducing the need for chemical fertilizers

3. Efficiently utilizes rainwater

4. Enriches the soil with nitrogen (about 12-15 units / acre) and organic matter

5. Improves the olive grove’s microclimate

6. Minimizes soil leaching and groundwater pollution

7. Reduces root system suffocation

8. Increases the porosity / drainage and aeration of the soil

9. Hosts beneficial insect fauna

10. Averts problems with weeds due to the rapid germination of the vetch and its allelopathic effect

Filled gaps

Vetch can store enough nitrogen in its root system to suffice for each olive tree for almost two years. This means farmers both save money by reducing their need for inorganic fertilizers, and reduce the amount of nitrogen leaching (which means the soil’s nitrogen is washed away in surface water and underground water, so it pollutes the water and cannot be used by the plants).

Limitation

Adequate rainfall after sowing is essential for the successful germination of vetch; this is usually not a problem during the winter in Greece. If there are weeds other than Oxalis pes-caprae in the olive grove, they must be cut before sowing.

Next steps/potential extension

If desired, the vetch crop can also be harvested for use as animal feed. Co-cultivation with cereals such as barley, in addition to the vetch, can offer even more benefits. The vetch can climb on the cereals, and the cereals can be used as animal feed.

Find out more

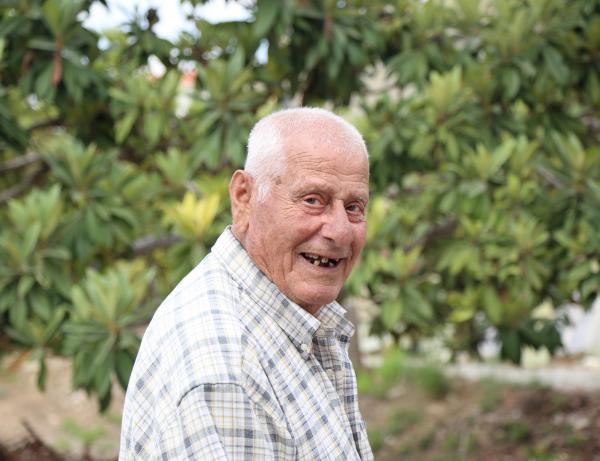

Spiros Lionakis, PhD

Emeritus Professor of Arboriculture

Hellenic Mediterranean University

slionakis@hmu.gr

LINK TO THE COMPLETE GREEK INNOVATIONS CATALOGUE (EN)

In the next Episode we will deepen and explore the innovation related to olive tree-avocado intercropping.

In parallel, we will start to introduce additional LIVIGAGRO innovations identified for the Lebanese and Jordan context, stay tuned...