LIVINGAGRO for Mediterranean agroforestry - Discovering Greek innovations included in the dedicated Catalogue, Episode 5

THE LIVINGAGRO INNOVATIONS CATALOGUE FOR GREEK AGROFORESTRY

Having identified potentially useful innovations, the partners of LIVINGAGRO project developed a dedicated Catalogue intended to provide an overview of some of the innovations that may be useful to stakeholders involved with multifunctional olive systems and grazed woodlands, in order to help bring together economic stakeholders and innovators who may be able to collaborate to solve common problems. This activity included assessing the stage of readiness of a potential innovation, as well as which type of challenges it addresses. Taking into consideration the needs expressed by stakeholders, the research team of the Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Chania (MAICh) and the technical team reviewed the information provided. Following this review, the working group went back to the innovators to address questions and fill in gaps, then incorporated the responses into the innovation descriptions.

Introduction to section 1 of the Catalogue concerning the re-use of traditional practices in agroforestry

In agroforestry, trees or shrubs are grown in or around pastureland and/or agricultural crops. Silvopastoralism, a type of agroforestry that combines livestock grazing and trees, was and still is a traditional land use system in many areas. For example, in Xeromero, Aetoloakarnania in western Greece, livestock breeders have used the valonia oak forest for grazing as well as collecting acorn cups from the oaks for use in the tanning industry. Agrosilvopastoralism is another kind of agroforestry where livestock is introduced in the field after the completion of the annual crop. On the island of Kea in the Aegean Sea, farmers used to grow cereals and legumes between trees for both human consumption and as feed for the animals. Greek olive farmers have also traditionally grown annual crops for the market or for grazing animals among their trees - or simply allowed livestock to graze on wild plants in the groves. Lately, there has been a gradual abandonment of this kind of combined land use, with a preference for monoculture, such as olive trees grown alone.

However, using forests and olive groves for multiple purposes has many benefits. For example, it ensures a steady and enhanced economic return every year, with a reduced risk of losses due to weather conditions or other types of hazards. Agroforestry can also increase biodiversity, reduce the impact of pests, enrich soil nutrient content, reduce erosion, improve carbon sequestration, and help reduce the risk and severity of forest fires. For these reasons, a return to productive old ways can become a useful innovation that allows farmers and livestock breeders to both increase their incomes from the production of high quality products, and help preserve valuable forest lands and olive groves using sustainable practices.

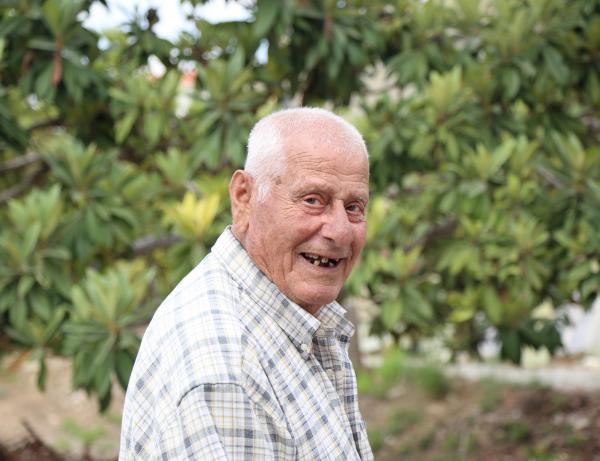

Presentation of Innovation 5: Olive tree, wild asparagus and free-range chicken polyculture

Background

Olive trees used to be cultivated with other crops and grazing animals on the same land. Crop specialization led to the abandonment of such polycultures in most cases, resulting in olive monocultures with frequent soil tillage but no cover crops or manure application. This caused decreased soil fertility and increased erosion, especially on sloping terrain. To prevent further damage, temporary or permanent green mulching is now often adopted. If a green cover must be maintained, why not use something that can produce additional income? Wild asparagus (Asparagus acutifolius) is a naturally occurring perennial vegetable that grows well in the moderate shade under olive trees. Its spears have been consumed from time immemorial, but the plant is not usually cultivated. However, its cultivation in an olive orchard provides an opportunity to increase income and productivity. Moreover, chickens in the same orchard can further increase farmers’ income, as well as taking care of weeds the asparagus makes it difficult to eradicate otherwise.

Keywords

Olive trees, olive growing, olive production, wild asparagus, asparagus, free-range chickens, polyculture, agroforestry, life cycle assessment, environmental impact, weed management, fertilization, meat, poultry

Methodology

Asparagus plants can be cultivated along the tree rows, leaving the alley free for the movement of machinery. They can also be cultivated between the rows, but this may limit the type of equipment that can be used in the orchard. The presence of asparagus plants makes weed control in the olive orchard more difficult. However, livestock can provide good weed management, as well as fertilization. Large animals are mostly incompatible, so smaller animals should be preferred. Free range chickens represent one good solution: they do not harm the asparagus plants or the olive trees. (They can destroy olive suckers when they first emerge and are tender: this is an added bonus.) Two cycles of 1000 meat chickens per hectare (ha) can be raised in the olive orchard: one in the spring, before and/or after the asparagus harvest (but not during the harvest), and one in the autumn (the two seasons when weeds grow and need control). During the summer and winter months, weeds do not grow significantly due to drought and cold respectively, at least in Mediterranean-temperate climates, so no control is needed. This gives the orchard a break from grazing pressure and provides enough time for natural sanitation, thus avoiding a concentration of parasites. In other climates, the period for the cycles can be adjusted based on when there is greater need for weed control.

Specifications

Wild asparagus is perennial; once established, it does not required soil tilling, which helps prevent erosion. Asparagus plants can be transplanted in spring or autumn along the tree rows at 2.5-3 plants per meter of row (4-5 thousand plants/ha). If cultivated also in the alleys, rows should be at least one meter apart (20-25 thousand plants/ha), or farther apart if appropriate for the machinery used in the orchard. Young plants should be irrigated during the first year, either regularly or when necessary. Afterwards, they should be able to cope with natural rainfall as well as the olive trees. If the trees are irrigated, the same (drip) irrigation system can be used for both the trees and the asparagus, optimizing the investment. Manure or fertilization with other organic materials is highly advisable for the asparagus plants and will benefit the trees as well. Wild asparagus plants become productive after about 2-4 years from transplanting, and the yield for well-cultivated plants is around 50-100 grams/plant, thus about 200-500 kg/ha with plants along tree rows or 1000-2000 kg/ha with plants also in the alleys.

Meat chickens should be allowed to range from the age of three weeks until they are ready for the market (about three months later for the slow-growing breeds that are more suitable for free-range systems). Good fencing against predators is usually necessary. A guard dog can also be very effective against predators. Two cycles of 1000 chickens/ha will provide complete weeding and fertilization for the orchard. Despite grazing, chickens will consume almost as much feed as they would without grazing, but meat quality and animal welfare will be increased while cultivation costs (for weeding and fertilization) will be reduced.

Impact

A life cycle analysis has shown the great environmental benefits of this polyculture, demonstrating that by providing natural weeding and fertilization services, the chickens very significantly reduce the environmental impact of olive cultivation. Economic analyses are being carried out, but it is already clear that this polyculture increases overall yield per unit area by producing more crops on the same land. Thus, it should provide more income than the separate cultivations.

Filled gaps

Polycultures are often more productive and better for the environment than monocultures, but only when the right combinations of crops are used. Wild asparagus appears to be a good understory crop in olive groves. However, intercropping complicates weeding and fertilization management. Using free-range chickens to do both jobs is a natural, cost-effective solution which also provides additional yield from the same land. Free-range animals need shelter against the weather. Olive trees provide such shelter, improving grazing time and range, as well as animal well-being. To summarize: the combination of olive trees, wild asparagus, and free-range chickens can benefit the olive grove and the livestock as well as increasing farmers’ income.

Limitation

It may not always be convenient to diversify production on a small scale, especially for livestock operations. Fencing is usually necessary and costly. Slow-growing chicken breeds are better grazers, but they have low feed conversion efficiency, so their meat has higher production costs and a greater environmental impact. For effective weeding and fertilization, grazing should be uniform. This requires moving the chicken housing often and/or managing the animals to encourage uniform grazing. Otherwise there will be overgrazing and soil compaction and pollution in some areas, and insufficient weed control and fertilization in other areas.

Next steps/potential extension

Selection for breeds that combine sufficient grazing abilities with greater feed efficiency is desirable. Chickens might positively interfere with the olive fly cycle, destroying maggots in the soil, as well as possibly controlling asparagus beetles or olive weevil, but more research is needed in these areas. More work could also be done to promote the marketing of sustainable agroforestry products, so they could bring farmers even better prices. It would be useful to explore ways for farmers to work together to create the economies of scale necessary to get the greatest benefit from this agroforestry system.

Find out more

Adolfo Rosati, PhD

Council for Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA)

Spoleto, Italy

adolfo.rosati@crea.gov.it

Presentation: LINK

Leaflet: LINK

Video (IT): LINK

Free manual (IT): LINK

LINK TO THE COMPLETE GREEK INNOVATIONS CATALOGUE (EN)

In the next Episode we will deepen Section 2 of the Catalogue "Intercropping and Preparing for Climate Change in Olive Grove" and explore the related identified innovations