Lebanon: NEX-LABS Best Practices in the Water, Energy and Food (WEF) highlight the importance of Institutional Structure and Open Innovation Framework.

During the past months, NEX-LABS project partner countries have worked with an incredible commitment to defining a list of their country-specific best practices, which are helpful to build a resilient, sustainable, and inclusive Mediterranean ecosystem for water, energy and food security.

Best practices are a fundamental ingredient to building a catalogue which can be useful for policy building and for improved local entrepreneurship and community resilience.

The survey conducted in Lebanon, together with research papers, helped define two features of the country’s sustainable development in the nexus of water, energy and food:

- Institutional Structure.

- Open Innovation Framework.

Concerning the institutional structure, Lebanon recognises the importance of solid academic and research institutions.

The education system in Lebanon is centralised and all public education establishments are regulated by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education in Beirut, which oversees the system through the regional education offices. Lebanon's emphasis on education is evidenced by the existence of three active ministries relating to educational matters. They are the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport; the Ministry of Vocational Education; and the Ministry of Culture and Higher Education. However, the educational system and its administration are still highly centralized in the country despite continuous efforts to give more control to regional and provincial departments. Instead of only one ministry of education controlling everything, now the government has three ministries that control all important aspects with regard to the educational system in the country and the way it is financed.

The Educational Center for Research and Development is an autonomous body under the Ministry of Education and Higher Education. The Centre's tasks include:

- drafting academic and vocational curricula for pre-university education,

- making any necessary adjustments and implementing these programmes,

- research in education,

- provides pre-university teacher training.

Higher education in Lebanon is provided by technical and vocational institutes, university colleges, university institutes and universities. Only one of these institutions, the Lebanese University, is a public institution. Private and public institutions come under the aegis of the Ministry of Education and Higher Education. University colleges, university institutes and universities fall under the responsibility of the Directorate-General of Higher Education. Cooperation in higher education between the European Union and Lebanon includes the Erasmus Mundus, Tempus IV and Marie Curie programmes.

The country is working to value its technical expertise and know how in the water, energy and food nexus. According to the paper published in 2016 Building the case for a Water – Energy – Food nexus governance study in Lebanon “When considering the application of the nexus it is important to understand the region under study, as the availability and tradeoffs of the different resources and from one scale to another – temporal and spatial. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has one of the highest water scarcity levels (Paul, Reig, Maddocks, & Gassert, 2012) in the world because of the pervasive aridity in most of the countries. However, it is very rich in natural gas and petroleum, where it has the highest oil reserve in the world (Birol, 2006). Lebanon, which is part of the MENA region, contradicts the physical state of most countries in the region. It has relatively high available renewable water resources per capita per year, but is low on energy sources such as natural gas and oil. However, Lebanon is still facing water and energy shortages and imports more than 80% of its food needs. These are further aggravated by climate change impacts, high population densities and rapid urbanization rates, influx of war refugees, and sectoral mismanagement. Agriculture in Lebanon is the highest consumer of available freshwater, consuming nearly 60%, while the remaining 40% are distributed amongst domestic use (29%) and the industrial sector (11%) (MoE/UNDP/ ECODIT, 2011). The energy sector is able to meet 77% of the total demand with the remaining 33% being provided by private generators on local levels. Only 4.5% of energy in Lebanon is generated by hydropower plants while 95% is generated by thermal plants (Ministry of Energy and Water, 2010a). Lebanon is a net food importing country where 20% of the total demand for food is produced locally and the rest is imported. Nearly 44% of processed food, 30% of livestock and 16% of crops are imported (MOA, 2009).(…) The interdependencies of the Lebanese water-energyfood (WEF) resources are evident in the various sector and national plans, strategies, and projects. One of the physical forms of the interlinkage of the three sectors are dams and their associated hydropower and irrigation schemes. (….) Nearly 50% of irrigated lands are surface irrigated, with the remaining 50% divided among 30% sprinklers and 20% drip (MoA et al., 2012). Implications of such methods of irrigation are a tradeoff between water consumption and the use of energy, as the energy intensive methods save water, whereas waterintensive ones use up very little energy. The use of machinery in agriculture is another form of the food energy interlink that varies by the size of the holding. Most small-sized holdings tend to use simpler and cheaper machinery to assist in cultural practices. The most used machinery is the truck used in transporting the produce, and power generators for pumping and refrigeration (MoA et al., 2012). (…)”

Another asset is the interest by international donors in the Lebanese green and environmental sector. Climate finance, as referred to by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), is a myriad of local, national or transnational financing intended to support climate mitigation and/or adaptation actions. It can be drawn from public, private or alternative sources of financing, and can be provided bilaterally or through multilateral funding organizations in the form of development aid, private equity, loans, or concessional finance to developing countries. The UNFCCC’s financial mechanism is entrusted to the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) (both managed by the GEF), the Adaptation Fund (AF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), with the first and the last being by far the largest in terms of funding resources. Established in 1992, the GEF helps developing countries to meet the objectives of the international environmental conventions. It has provided over USD5.7 billion in grants and mobilized USD45.3 billion for more than 1,000 climate change mitigation and 330 adaptation projects in 160 countries. The GCF, established by the UNFCCC in 2010, channels climate finance to developing countries, to meet the adaptation and mitigation goals of the Paris Agreement. It has so far committed USD5.6 billion to 129 approved projects to date (April 2020). These supports fall within global efforts in mobilizing large-scale investments at a global level, estimated at USD280 billion and USD500 billion per year by 2050 (UNEP).In Lebanon, key international donors for climate change projects include the GEF, the EU, UNFCCC, World Bank, and EBRD among others. Financial support has been received in the form of grants, loans (including concessional ones), green bonds and credit lines. Lebanon received a total of USD 269,435,749 from the GEF Trust Fund to support 51 environmental projects since 1995, out of which 12 are national climate change projects. Lebanon also benefited from 27 regional/global projects under GEF, one of which was specifically dedicated to climate-change in 2000: The “Capacity Building for the Adoption and Application of Energy Codes for Buildings” project for Lebanon and Palestine (USD195,000 allocated to the Lebanese component, in addition to USD510,000 for shared components). As for the SCCF managed by GEF, it has contributed USD7,147,635 for the Smart Adaptation of Forest Landscapes in Mountain Areas (SALMA) project by the Food and Agriculture Organization. GEF also supported the Climate Smart Agriculture (AgriCAL) project, with a budget of USD9,282,720 via the AF. The Green Climate Fund’s current contribution (USD 828,159) to Lebanon serves the Readiness Project with the South Centre operating as the Delivery Partner. Support in the form of grants has also been channeled from OECD countries to Lebanon for policy formulation, institutional support and education and awareness in the fields of forestry, energy, water supply and sanitation, which are directly and indirectly related to climate change. The Lebanon Trust Fund (LRF) funded in 2013-2015 the National Action Programme to Mainstream Climate Change into Lebanon’s Development Agenda (USD500,000), to improve climate change governance and coordinate climate change initiatives. The Low Emission Capacity Building Project (LECB) implemented by the MoE received support from European Commission, the Australian Government and the German Federal Government amounting to USD1,103,000. to develop a greenhouse gas emission national inventory system, Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs), and the establishment of a Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV) system and was completed in 2018. Lebanon’s Nationally Determined Contribution Support Programme (NDCSP) with USD887,500 to improve the assessment, achievement and reporting of the country's NDC submitted in 2015. For funding on sectoral projects, please refer to Chapter IV of Lebanon’s Third Biennial Update Report.

Always according to the Climate Change governmental page, “ While these funded projects provide an overview of climate flows in Lebanon, further efforts need to be deployed to optimize climate finance mobilization, tracking and coordination. Identifying the country’s needs, finding innovative ways to mobilize funds, and coordinating priorities with donors remain essential pillars to attracting climate finance in Lebanon. This must also be accompanied by unified climate finance criteria across all sectors to homogenize tracking methods and inform future endeavours in this area. “

To further build resilience, Lebanon invested in entrepreneurship support institutions aiming to create a humus where start-ups could tackle some of the WEF challenges. Lebanon has truly built an ecosystem composed of:

- INCUBATORS AND ACCELERATORS: Incubators and accelerators advise and support startups with a range of services including business advisory, mentorship, training workshops, and office space. Today there are 11 incubators and accelerators in Lebanon.

- MENTORSHIP PROGRAMS: Mentorship programs provide start-ups with access to mentors both locally and internationally.

- MEDIA PLATFORMS: Dedicated startup media platforms are useful in getting the right exposure and marketing.

- TRAINING INSTITUTIONS: A number of institutions in Lebanon offer training, coaching, and technical support to startups.

- CO-WORKING SPACES: A number of co-working spaces in Lebanon can serve as a cost-effective alternative to traditional offices.

Social entrepreneurship is essential to the Lebanese economy and plays a major role in creating and sustaining a better socio-economic environment. However, it needs a proper ecosystem to grow where social innovators can be mentored, financed, and supported. This is addressed and solved through Berytech’s Impact Rise program – Lebanon’s pioneer social entrepreneurship scale-up program launched in October 2019 and funded by MEPI. Since then, Lebanon has been suffering from the biggest economic crisis. And after the disastrous Beirut Blast, many people have lost their jobs. Economic inflation is affecting businesses and decreasing the number of startups willing to invest in this country. For further information check some of the chosen 7 start-ups which Berytech is asking support for consult the Berytech Impact Rise Social Entrepreneurship Program, not only environmental, but also social. In addition to these projects, the Ministry of Commerce and Trade organizes several entrepreneurship events Francophone Entrepreneurial Women’s Award (Berytech) | Global Social Venture Competition (Berytech) | Startup Booster Track (Berytech) | Agrytech (Berytech) | MSFEA (AUB) | Darwazah Student Innovation Contest (AUB) | NVC (USEK) | SocialChallenge (USEK) | GEW | Young Entrepreneurs Competition (INJAZ Lebanon), all which can be consulted at this link: https://www.economy.gov.lb/en/services/support-to-smes/entrepreneurship-competitions.

Two best practices which are also evidenced as useful are adequate geographical and climate conditions to develop and implement solutions in the WEF nexus, and ultimately the integration of social and environmental framework across projects to track social and environmental impact.

The second pillar of Lebanese transformation to a sustainable WEF nexus is developing an open innovation framework. Within this pillar we find processes, collaborations, clusters, technology transfer, expert networks and multiple stakeholder community building.

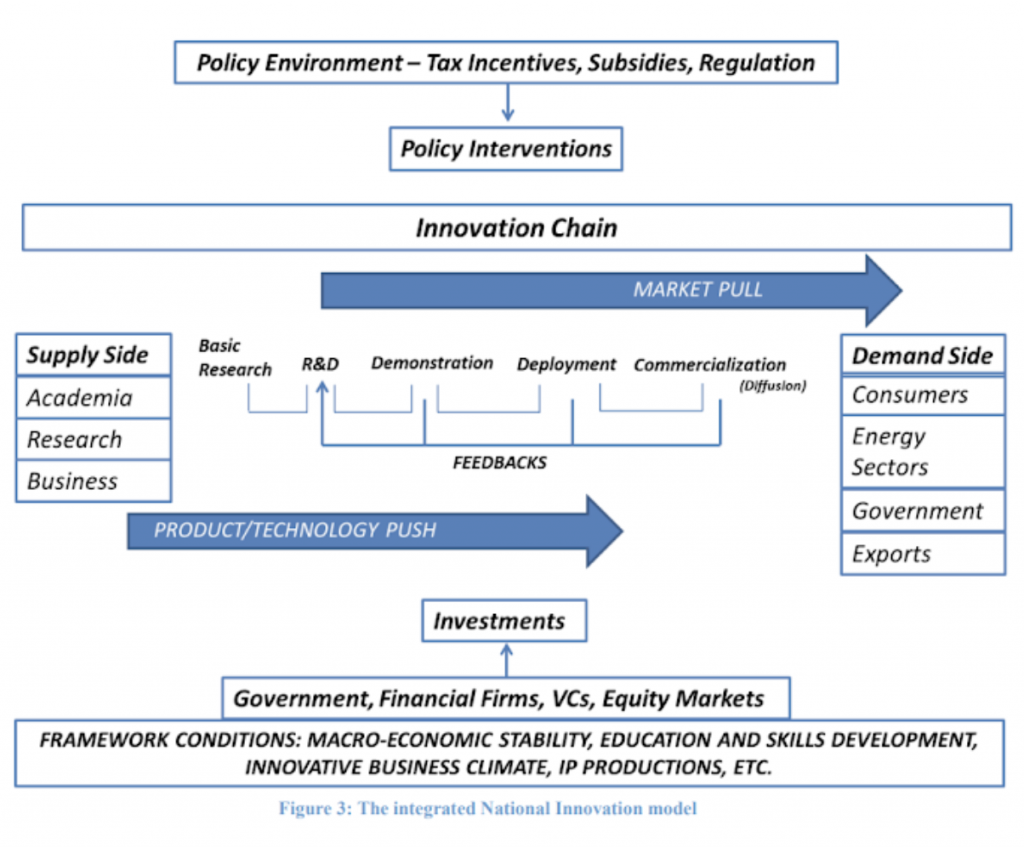

In 2016 a research was published show casing a model for the National Innovation System as a set of 5 pillars or 5 sub-systems:

- The Innovation Supply Side, performing the Knowledge Generation and Technologies Production function. ∙ The Innovation Demand Side, performing the Knowledge Diffusion and Market Absorption function.

- The Linking Intermediaries responsible for the Knowledge and Technologies Transfer.

- The Innovation Ecosystem which include the Human Capital and the Business and Financial Environment.

- Policy Framework setting the Government role and interventions.

The paper illustrated how the National System should be working to deliver in quality and practices:

With this research dating 2016, there are some failures evidenced, and the model for investigating reasons for ‘innovation failure’ in Lebanon must take into account the following central context specific factors.

- Infrastructural Failures. The failure of national infrastructure such as the provision of telecommunications networks, energy provision failures, and dated and slow transportation links.

- Governance Failures. Includes the Lebanese State’s failure to implement its own policy provisions; enforcing the rule of law and equality before the law; regulations; and smoothing cooperation between its own entities and the interaction between the public and private sectors.

- Capabilities Failures. These failures include limitations at the level of training and research provision provided by Lebanese universities and other relevant bodies.

- Sociocultural Failures. Lebanon is a risk averse society thanks to the political climate and it is a society enjoying too much capital. Innovation demands risk taking, grand visions and the courage to face multiple failures and undertake repeated experiments to reach and achieve an end. This courage is what separates those who succeed and those who fail.

The Euro-Mediterranean Charter for Enterprise Charter, a set of policy guiding framework which aims at improving the SME environment of 9 Mediterranean counties, referred to as MED countries (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Syria and Tunisia) has functioned, since its adoption in 2004, as a guiding document for MED governments’ policy building towards the private enterprise sector. It is structured under 10 policy dimensions, as stated below.

- Simple procedures for enterprises

- Education and training for entrepreneurs

- Improved skills

- Access to finance and investment-friendly taxation

- Better market access

- Innovative firms

- Strong business associations

- Quality business support schemes and services

- Strengthening Euro-Mediterranean networks and partnerships

- Clear and targeted information

At page 49 of the report the 2012 Lebanese profile of its Innovation System showed the following:

Main weaknesses

- Political instability

- Difficult political environment

- Limited expenses on education

- Limited expenses on R&D

- Weak collaboration between universities and industries

- Inefficient infrastructure: Telecommunications, electricity , transport

- Royalty fees receipts almost inexistent

And Main strengths

- Very good tertiary education

- High FDI inflows and outflows

- Strong creative goods and services

- Very important cultural and creative services export

In summary, the report oulines the following observations:

- The inputs to the LNIS (Lebanese National Innovation System) are limited and outputs almost inexistent,

- Lebanon is facing a very challenging governmental issue in terms of governance, strategizing, planning, coordinating the different institutions and enacting laws,

- Limited collaboration between the two main pillars of the LNIS universities and industries,

- High creativity and cultural exports,

- Excellent educated university graduates, and

- Strong banking sector.

Based on the country profile for Lebanon as featured in the Report on the implementation of the Euro-Mediterranean Charter for Enterprise (2008), some priority areas were identified.

Institutional Policy Framework. It is important for Lebanon to reactivate the enterprise policy agenda (set back in 2005) in order to fit it in the new political and economic contexts emerging in this sector. Integrating SME support programs and re-launching of consultations with the private sector is needed in order to redefine priorities and update future work programs.

Regulatory Reform. Work should proceed towards simplifying administrative procedures (MoET, MoF, and OMSAR32) so as to relieve SMEs from imposing administrative constraints.

Business Support Schemes and Services. Business development networks and centers need to be expanded in the country in order to use them as channels for executing government and donor-funded programs alike.

Human Capital. Based on the scores for Dimension 2 Education and Training for Entrepreneurship, the assessment showed that there is a gap in terms of policy and delivery in lower and upper secondary levels of education, with a limited number of projects that promote entrepreneurship for students early on in school.

Therefore, the report recommended to initiate dialogue between the private sector, NGOs and universities for a collective effort on determining how to promote entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial learning in schools. This could be done by providing school guidance and counseling services.

To promote a fertile environment for innovation Berytech, through THE NEXT SOCIETY Advocacy Panel, has been leading on setting a national innovation strategy for Lebanon since 2017, as part of THE NEXT SOCIETY action plan initiated by ANIMA Investment Network and implemented in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine and Tunisia with the financial support of the European Union.

In an article published in May 2020, Berytech put together 29 Actionable Recommendations To Boost Technology Transfer & Commercialization In Lebanon. Acting as a Task Force at the national level, the objective of THE NEXT SOCIETY Advocacy Panel is to oversee the formulation of the innovation roadmap, its implementation, evaluation and update, with the objective of strengthening the national innovation system, fostering coordination among actors involved and improving concrete instruments of the innovation policy. The panel is composed of Lebanese private sector representatives and investors, innovation stakeholders, relevant Ministries and their agencies, the European Union Delegation to Lebanon as well as academic experts. Findings have highlighted that, while Lebanese researchers may be good publishers, there is a need to incentivize them and create reward systems to push them to develop projects with commercialization potential. The Lebanese ecosystem is challenged by the lack of funding for applied research, lack of Intellectual Property (IP) policies and support as well as weak links between academic research and industrial needs.

“There is a need to plant the innovation seed in academia,” comments Krystel Khalil – Programs Director at Berytech and lead on the Advocacy Panels. “Most industries claim to be innovative, but they don’t even have an R&D department, which is crucial for innovation.” Therefore, there is a need to develop the technology transfer landscape and encourage the development of researches that address market needs turning them into commercial startups, or better, connecting them with industrialists.

“Connecting local research and industry, in other words technology transfer, is a major driver of value creation and innovation for MENA countries,” confirms Mathias Fillon, THE NEXT SOCIETY coordinator at ANIMA Investment Network. “We address it both at the micro level, through the Tech Booster acceleration programme supporting success stories of research-based start-ups, and at the policy level through the Advocacy Panel and technical assistance activities”.

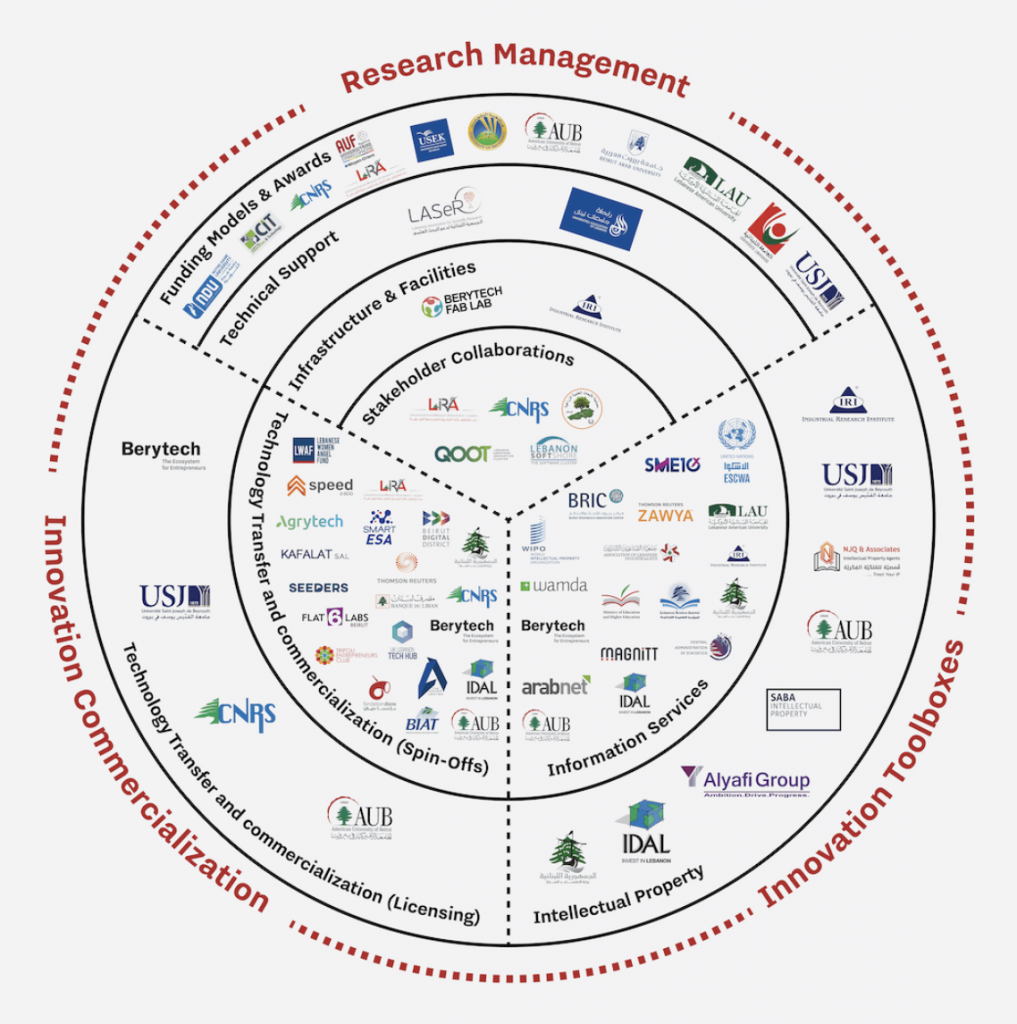

The Technical Assistance Report provides an analysis of the Lebanese technology transfer ecosystem, identifies its gaps, and proposes actionable recommendations to be implemented by the different ecosystem stakeholders of technology creation and valorization. The three pillars that make up the framework of this report and for which recommendations are made are:

Research Management, which is the process of turning research into market-ready creations, which includes the types of existing and needed collaborations between the different stakeholders, technical and financial support, and infrastructure.

Innovation Toolboxes, which encompasses the tools and knowledge needed to valorize new technologies.

Innovation Commercialization, which comprises three main tracks: (1) commercializing technologies via licensing, (2) selling and (3) spinning-off into ventures

Given that universities are key stakeholders in the technology transfer and commercialization ecosystem, the responsibility of revolutionizing this process in Lebanon, falls largely on their shoulders. The roadmap, as a concluding directory of the recommendations developed, is mainly focused on five universities: Lebanese American University, Saint Joseph University, American University of Beirut, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, and the University of Balamand.

The report concludes by categorizing the recommendations into three main sections: top-down actions, bottom-up actions, and support mechanisms. The roadmap follows a chronological order that each university is recommended to follow depending on the level of maturity and available resources.

The main goal is to transfer research into marketable products, whereby they can either be sold/licensed, or spin-off into a venture, which mainly requires top down actions. In the selling/licensing track, the roadmap unveils the steps needed to be taken, from the mapping of opportunities between university research and the different applications in various value chains, to matchmaking with the industry and the promotion of success stories. In the spin-off track, universities must ensure that they are providing their staff and students with the correct resources to support them in starting their venture.

All of this is likely to happen while the internal intellectual property policy is being developed, updated, and disseminated to students and faculty. In addition, several bottom-up activities should take place to strengthen and nurture the culture of innovation within universities, such as the changing of curricula, and the introduction of entrepreneurial extracurricular activities.

Finally, and in parallel, government and intermediaries play a crucial role as support mechanisms that encourage, directly and indirectly, the strengthening and efficiency of this process through policies, matchmaking, fund provision and facilitations, and more.

If you are an active player in technology transfer and would like to implement the best practices and framework to grow the ecosystem in Lebanon, please fill in this form to receive the full report.

Returning to the NEX-LABS WEF best practices booklet we find a list of other best practices such as:

- Open innovation process to support the development of solutions that address real market and industry challenges.

- Collaboration between academia and industries and co-creation of solutions 9. Engaging in regional networks and clusters.

- Availability of different programs supporting technology transfer and communication between various stakeholders.

- Existence of WEF targeted and specific networks of experts and mentors.

- Networking events and roundtables to foster the exchange of expertise and create collaboration and partnerships involving multiple stakeholders.

Download the NEX-LABS Best Practices Booklet here

For further research, please consult:

- International Association of Universities, Lebanon: Structure Of Higher Education System

- Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education

- Water, Energy, Food Nexus: An Outlook on Public Institutions in Lebanon Nadim Farajalla Patricia Haydamous Rana El Hajj Beirut, August 2016

- The LCEC: Blending LEEREFF and NEEREA Financing

- The South Centre: An Update on the Green Climate Fund

- The South Centre: Climate Finance Readiness

- Nationally Determined Contribution Support Programme

- UNDP Lebabon 2019 Climate Change Report

- NATIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEM IN LEBANON, Beirut Innovation Centre (2016)

- Video 29 actionable recommendations to boost the technology transfer in Lebanon (full version) Berytech 2020

- NEXT SOCIETY

- BERYTECH

- List of Arab Entrepreneurships including Lebanon