AQUACYCLE My Autobiography – Viewpoints on reuse of treated effluent resemble traffic lights!

Red light to reuse in Lebanon, orange in Tunisia and green in the province of Almería, Spain proved to be the concise outcome of the brainstorming session which was on the agenda of workshops with local communities in the respective countries where I am set to make my physical appearance.

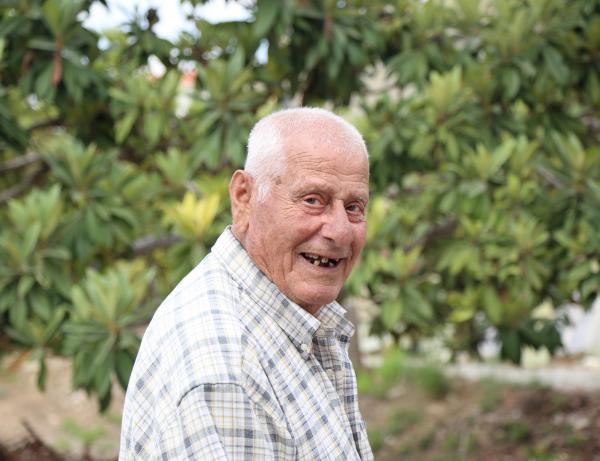

As I learned from the earlier interview with farmers Sergio and Maria Isabel in Spain to mark World Water Day 2022, the province of Almería is faced with a significant water deficit. Hence, it came as no real surprise to me that the participants were unanimous about the importance of the reuse of treated effluent.

The decision by my Spanish co-creator teams, PSA-CIEMAT and ESAMUR, to organize the event in Tabernas in the province of Almería, was motivated by the fact that the reuse of treated effluent in this part of Spain, as around most of Europe, is still in its infancy. This created the opportunity to showcase the high level of reuse in the neighbouring region of Murcía.

The event also created the opportunity for my Spanish co-creators to share the first results of me having made my physical appearance in Blanca nearly one year ago. Needless for me to add: these results established beyond any doubt of my having several advantages over my distant cousins who operate on the conventional process of activated sludge. Editor’s note: AQUACYCLE’s vanity obviously was being spurred on with these first results, but more on these indeed highly promising results will be shared at the appropriate time.

The municipality of Tabernas is located on the edge of the famous Tabernas Desert, the filming location of many feature films and TV series. With travel restrictions lifted, I did take some time to visit the three film sets in the area: Fort Bravo, Western Leone and Mini Hollywood!

I was impressed that simply everyone attending the workshop reported to have knowledge of the existence of alternative, non-conventional sources of water. Moreover, the participants had a clearly positive perception about the use of treated domestic effluent for irrigation. Evidently, I fully concurred with their viewpoint that this practice is necessary and essential for the future water sustainability as well as of great agronomic, environmental, and economic value.

Yet another interesting outcome I picked up was that most of the participants (83% to be exact) considered such reuse to be a safe practice if an appropriate water treatment is applied; reuse regulations are complied with; and a strict and complete surveillance plan is in place.

Some of the participants opined that treated effluent can be safer as compared to a conventional source, i.e., a surficial source or a groundwater source, given the strict EC regulation in force for the reuse of treated effluent in agriculture and the controls that are applied to ensure conformity with this EC legislation.

More than half of the participants (60%) agreed that treated domestic effluent could be made available also for other purposes than irrigated agriculture, such as for industrial purposes, aquifer recharge and the irrigation of golf courses and urban greening. Yet, a sizeable number (40%) held the view that treated effluent should be made available exclusively for the irrigation of crops due to the notion that intensive agriculture is the economic engine of the Almería Province in Spain.

I was all ears once more when the participants voiced concern about the lack of information made available to society in general about wastewater reuse applications, and about the controls that are in place in Spain to ensure such reuse is safe, and in compliance with EC regulations in force.

In a sharp contrast to the unanimous demand for the reuse of treated effluent by the participants in the workshop in Spain, their counterparts in Bent Saidane which is located in the Zaghouan Governorate in Tunisia, and in particular the farmers, proved much more reluctant to use treated effluent to serve their irrigation needs.

Obviously, I immediately took queue and pleaded with my co-creators in Tunisia, CERTE and CITET, to invite the participants to explain the reasons for this reluctance in more detail. The farmers duly complied and shared the view that the handling and use of treated wastewater to food crops carries a variety of public health risks. The participants also cited potentially harmful compounds and pathogens found in treated wastewater; the risks of exposure of the farmworker to these harmful substances, and the risks to soil properties and groundwater quality.

The participants also referred to the notion that public perception affects the economics of a product: if a product is considered not desirable the value assigned to it by the consumer is low. Yet, the participants were aware that some farmers have been making the switch to treated wastewater whenever the pressure on conventional sources became greater, and especially when the conventional source they rely upon becomes inaccessible or too costly.

From the ensuing discussion I learned that farmers in the Bent Saidane area do take their time to settle their bills for the conventional water they use, forcing the Agricultural Development Group (GDA) to sell part of the water to the drinking water utility SONEDE to balance their budgets. I also picked up that despite the economic and environmental benefits of switching to treated wastewater reuse, farmers are generally unwilling to pay for the supply of treated effluent.

Although I was with the conviction that religion is a commonly cited reason for opposing the use of treated effluent, this aspect had not been raised, neither by the Imam of the village, present at the workshop, nor by any of the other participants. What did emerge from the discussion is the view that society’s lack of trust in various levels of government and in the private companies that are involved with the operational running, maintenance and monitoring of wastewater treatment facilities in Tunisia is a major obstacle in gaining acceptance for initiatives aimed at the reuse of treated effluent.

I did take heart when, despite their reservations to the reuse of treated effluent, farmers were found willing to share their expectations if I was to make a physical appearance among them. Editor’s note: in December 2022, the tender for my physical construction in Bent Saidane was relaunched for a third consecutive time after, much to my regret, also the second tender process had been met with a negative appraisal by an inter-ministerial task force in charge of assessing procurement processes by public entities.

Due credit must be given to the organizers for attracting wide media coverage of the workshop which was covered by the Albiaa news channel as well as through an interview with Dr. Hamadi Kallali, CERTE Teamleader, on Cultural Radio and on Tunisia’s National Television Station TV1. Conducted in French, the interview was uploaded to my channel on YouTube with subtitles added in English.

Meanwhile, my co-creator team in Lebanon, the Lebanese University, opted to organize the workshop at Nawfal Palace in the Al-Tell District of Tripoli. This gave me the opportunity to not only appreciate the splendid interior of this majestic building with its expansive library, but also to visit the nearby Clock Tower among other truly inspirational historic buildings in this part of Tripoli.

If the farmers and local community representatives in Bent Saidane had proved reluctant to the reuse of treated effluent, the unanimous viewpoint of their counterparts in Lebanon proved stronger still: “We are not likely to accept reuse applications of any type since the topic of sewage water draws fear among our society!”.

Not surprisingly, a foremost outcome of the workshop was the renewed appeal by the Lebanese University team to the country’s policy- and decision-makers to address the country’s poor record in the sanitation sector. In his interview with the news channel Al-Araby Al-Jadeed on 24 October 2022, Prof. Ahmad ElMoll went on record to establish a causal link between the poor wastewater management and the spread of cholera and disease in Lebanon. From this interview, I learned that the largest wastewater treatment in Tripoli only separates the solid from the liquid waste in the wastewater stream, following which the solid part is sent to landfill and the liquid part is discharged into the Mediterranean.

I am pretty confident that society at large would be aware that in a conventional wastewater treatment system, this process is designed only as a pre-treatment stage, i.e., a stage which is prior to actual treatment stages. I guess you would be referring to a Neanderthal cousin in your own family tree as a translation of “such a rather primitive system”, given there is no actual treatment in place?

In fact, several additional arguments were brought to the fore by the participants substantiating their ingrained fear towards the reuse of treated wastewater. These included the following:

- Sewage pollutes groundwater. Many Lebanese homes, villages and even cities depend on artesian wells for drinking water. At the same time, dwellings are relying on a septic reservoir to store sewage which substantially increases the likelihood of polluting these reservoirs’ underground surroundings, including the groundwater that is being tapped by the artesian wells.

- Existing sewage plants are not operational. Lebanon has witnessed the construction of sewage treatment plants in several towns and villages. Yet, already within the span of a year or two, these plants become abandoned places, and the investment and construction costs have gone to waste.

- Farmers will not accept the idea of reuse. The participants acknowledge that treated effluent can provide a non-conventional source of water which can be reused for irrigation in agriculture, but argue that farmers will refuse to use it. The question of what to do with the treated effluent when it is not needed during the winter season is also raised as an obstacle to raise financial investment towards the construction of treatment plants.

By this time, to be perfectly honest, my earlier jubilation on the award of tender for my construction in Deddeh, south of Tripoli, had all but evaporated. Yet, I took heart when the participants continued reflecting on the wider gravity of the country’s poor water management strategies which called for urgent solutions to be found. One by one, the participants started to bring arguments which saw the reuse of treated effluent as becoming necessary. Realistically, the reuse of grey water may well present itself as the most cost-effective solution to overcome the water scarcity and the desertification of the region, which is being further aggravated by the impacts of a changing climate.

A participant speaking on behalf of the Tripoli municipality, considered that everyone is predicting that the region is destined for a war over water. He referred to the book entitled “Le dérèglement du monde”, the disruption of the world, penned by the Lebanese French writer Amin Maalouf, in which the internationally acclaimed writer asserts that one of the greatest dangers threatening the whole world is climate change, and that alternative sources of water and of clean renewable energy must be sought.

Another participant asserted that the research carried out under my name, AQUACYCLE, is most purposeful, particularly as it is not confined to desk and laboratory research but aims to demonstrate my functioning as an eco-innovative wastewater treatment system under real-life conditions.

A representative from the Chemical Engineering Department at the University of Balamand, expressed his gratitude for having been invited to the workshop for two reasons: “First, I am from the town of Deddeh, so I am happy to see that a pilot wastewater treatment plant like this will be constructed in my town. Second, because I work in the field of wastewater treatment.” He shared his experience in treating sewage water from hospitals through an EU funded project: “Through our visits to Europe, we had the opportunity to see how they treat the wastewater there and specifically in Spain. We saw in Andalusia how they treat the wastewater from their largest hospital. The treated wastewater is then not only used for irrigation, but it is returned to rivers. This allows the treated water to be used by simply everyone, not only by farmers. Therefore, we hope to reach a higher level of wastewater treatment which will bring us multiple benefits.” In his expert opinion, the sludge that will be produced could be treated in a cost-effective manner given its potential to be used as a fertilizer, and thereby confirming that my mode of treatment will set a best practice example of the circular economy concept.

He emphasized that while the local community clearly does not wish to accept the idea of reuse, the farmer needs solutions to ease his burden: “You offer the farmer, in these difficult circumstances, a new source of water and organic fertilizer of high quality and low cost. These initiatives are now in their time, the farmer needs this type of solutions to ease his burden. If we start from a specific place, such as my town, and everyone starts to see and hear about this initiative, I think this will help people to accept and become convinced with the idea of reuse. If I was asked to pay money to try it out, of course I would refuse, anyone else would refuse too. But if you tell me that my neighbour is irrigating with treated effluent and he is satisfied with the results, and that I can visit him and see with my own eyes, of course I would be encouraged to apply it too. In the end, this approach will not only encourage neighbours but also nearby villages and municipalities to accept the idea of reuse. Usually when an idea is new to society, it may not be accepted among society. But when people have heard and become accustomed to a concept, they accept it and become more encouraged to apply it for themselves as well.”

His research colleague, the Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the Université Libano-Francaise (ULF), appealed for joint cooperation between universities, the municipalities and NGOs. He described Deddeh and Tripoli as one of the best municipalities in North Lebanon when it comes to cooperation with local residents and because of their active encouragement of actions such as those promoted under my name. He pointed out that while cooperation exists in all countries of the world, such cooperation had been regressing in Lebanon due to the country’s prevailing financial crisis. He also considered that since the university is located close to the pilot site at Deddeh, it could benefit from the reuse of the treated effluent for landscaping purposes of its 25,000 square metre ULF campus among other possible reuse applications.

Hence it came about that the eminent professors from three universities in the area of Tripoli, who as it turned out to have been long-time residents of Deddeh and its environs, resolved to find a way forward by joining forces. At the same time, they seized the opportunity created by the workshop to extend the invitation for joint cooperation also to the representatives of the local municipalities and of the NGOs who had joined the workshop in Tripoli.

Now my face could finally light up, from literally having witnessed a unanimous “No!” to the idea of reusing my treated effluent, the participants resolved that it was time to join forces to find a way forward to the poor situation in the country’s water and sanitation sector. Perhaps, at the end of the day, and with my construction finally having gone ahead at full speed in Deddeh, I would be witnessing “green light” to the use of my treated effluent after all!

The previous entry in AQUACYCLE’s logbook can be accessed through this link.

The first 12 entries in AQUACYCLE’s logbook were published in February 2022, which can be downloaded from this link.